Part #1: "Your chances of developing depression are 50/50."

The risks, and rewards, of prognostic disclosure.

Statistics are everywhere in my life: xG, likes, death tolls, email open rates and, yes, they’re baked-in to Substack, too.

Up until August 2023 I’d never even visited the GP, let alone been hospitalised. So my perception of health risk and medical stats was all tertiary and tangential. It happened to other people: people on the telly, people with chronic illness or old people who had had a ‘good innings’.

How quaint.

How naive.

We’re all familiar with the scenario of a doctor calling a patient into their office to deliver some catastrophic diagnosis, and then giving the ill person X years/months/weeks to live. It’s a well-trodden trope in pop culture, but apparently it happens every day in real life, too.

In the fairytale version, the ticking clock counting down to the protagonist’s demise is the key driver to living life to the fullest: travel, adventure, repairing broken bridges, discovery, enlightenment.

But what happens when that stat isn’t met with (toxic) positivity?

There’s a phrase for this sharing of information from doctor to patient:

Prognostic disclosure risk

The risk involved when a doctor shares prognosis-related information (e.g. chances of death, survival rates). This includes emotional, psychological, or decision-related consequences for the patient.

It needn’t be a terminal illness, though. Happily, it wasn’t terminal for me as I had already dodged those bullets days before when:

I was found, alive, on the side of the road.

Some very delicate brain surgeons kept a steady hand as they drilled and sawed into my skull.

Doctors told my Mum and Dad that I urgently needed to “turn a corner” during my pneumonia/coma days.

So, no more (near)death chat this time.

But I do have two clear examples of this risk bearing fruit from my experiences post-TBI (Traumatic Brain Injury). Both come from a place of deep-compassion, knowledge and expertise. And both have had outcomes which continue to ripple through each day of my life.

First up…

50/50

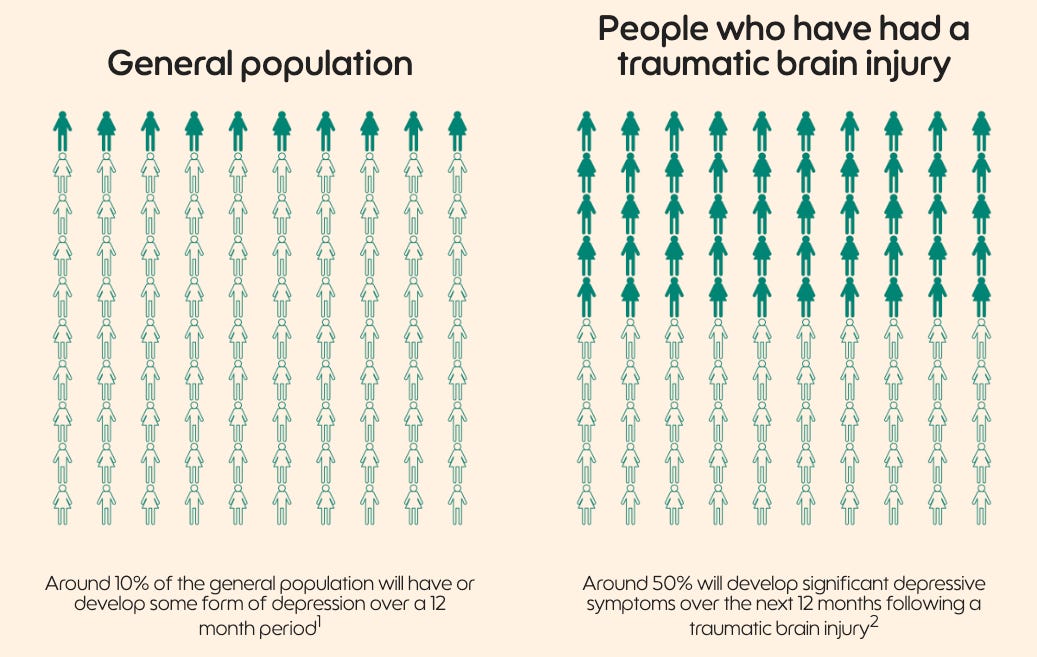

It has been estimated in many studies around the world that around 50% of people could develop depression after they have had a traumatic brain injury over the next 12 months.

In the general public, this estimate is around 10% over 12 months. In other words, there is about five times greater chance of developing depression and related problems such as sleep disturbance, tiredness, poor concentration and memory and irritability.

This was the stat shared with Holly and my family whilst I was still in the coma. But it was probably the short and sweet version: “he has a 50% chance of developing depression”.

The people delivering this cheerful message were running a new clinical trial called STOP-D and, as the name hints, it was designed to study/prevent post traumatic brain injury depression via daily doses of Sertraline (a very common antidepressant).

Basically, it‘s testing the theory of a preemptive strike against the morbs, using anti-morbs pills, on people who have given their heads a good shake.

For the study to work and be most effective and science-y, they needed to “recruit” (their words) patients as promptly as possible post-TBI. So they were getting a little stressed, I suspect, as my 19 day coma put me beyond their parameters for the ideal patient. I was, simply, too under the weather.

Holly and my parents had told them they’d rather I make the decision myself, so they had no choice but to wait and see when I’d wake up. But they changed the rules of recruitment for me, and then across the ongoing study itself. Large main character energy, I know.

And so, the day after I was brought out of the coma they were beside my bed, chatting, signing me up to the 18 month trial, taking my blood, delivering that cheerful 50% stat, asking me to spit into vials and remember five random words:

Lion. Purple. Church. Fabric. Door.

Now, draw the face of a clock with all the numbers. Then make it show as 10 to 2.

Next, connect these dots when A goes to 1 and B goes to 2 and so on.

In the past two weeks have you had thoughts of hurting yourself or others: every day, more than half the days, several days, once or not at all?

How much do you drink?

That sort of thing.

I was fastidiously conscientious throughout; a proper try-hard. I’m convinced my brain felt that not passing these ‘tests’ would mean another night in the Critical Care loony bin. So I concentrated harder than I ever did for my GCSEs or A-Levels.

Looking back, I put myself forward for the trail that day, whilst still in Critical Care, for a number of reasons:

I’m a people pleaser.

And these researchers seemed cleverer than me (with or without a brain injury).Depression is terrifying.

This feels like an obvious one. Best avoid it if you can.I’m selfish.

Free drugs to fix a likely issue with added (fast-tracked) support? Yes please.But, really, I’m a selfless medical pioneer.

Look at me dedicating my brain to the betterment of humanity. What a guy.

So, in late August, I was sent home with a big rattling tub of pills and told to take them every morning with my Weetabix. There were no obvious side effects. But perhaps that was the point? Or maybe it was just a placebo?

Either way, that 50:50 ratio would consistently pop back into my head. Every day I’d ask my brain: am I mentally well, am I just a normal-level of sad, should I be thinking about death this much, is this amount of crying usual?

After 30 years of cheering on the glass-half-full team, I was now very much focused on the empty half. The air above the liquid was gloomy. And I would wonder, for hour after hour, if I’d be better off not knowing my arse was perched on the fence between cheerful chappy and depression, waiting for a gust of wind to blow me one way or the other. Yep, in the least surprising newsflash of all time, recovery/life can be pretty bleak when you’ve had a bleed on the brain.

I’ll write about all the stuff that happened between leaving hospital and today elsewhere, so let’s fast forward 18 months to the end of the trial where, at my final check-in, I discovered I was the first patient to complete the STOP-D trial.

Go me. Whoopdeedoo. Etc.

I’m proud to have been a part of STOP-D. And for all the doom and gloom, I can honestly say I feel like it might have helped me. At the very least the chats, the check ups, the persistent questions about suicidal ideation and the physical act of taking antidepressants every day made me far more empathic to the human experience of others.

Whilst I don’t know if I’m a good person or not, I do know that my bump to the head has made me a better person than I was before. (Am I allowed to say that?)

And finally, before you go, what were those five words again?

Part #2 coming soon…

Things to look at/read/know:

STOP-D. Here’s the website for the trial I was part of. Unsurprisingly, this site didn’t exist when I was among the first recruits. But look how snazzy it is! I felt genuinely happy when I saw Shu-Jen’s name listed here. She was my ‘handler’ and she was great.

When I was recruited, the trial was basically bouncing around all the London hospitals with helipads, recruiting other 30-something males who had tumbled off their bikes and crumpled their skulls. We were basically the entire demographic. The study area as expanded now, but it’s still mainly men-of-a-certain-age who came in unconscious and wearing lycra.

And if you’re wondering. Apparently I can apply to see if I was on the placebo, or not, two years after the conclusion of the study. Some time to go yet…

For the first three months after leaving hospital I lived with my two-year-old niece. She was highly effective against the morbs. 10/10 would recommend.